Keep Debar Pond Forever Wild

With Pete Nelson

A proposal making the rounds in the halls of power at Albany would alienate from the public domain one of the most scenic spots in the Adirondack Forest Preserve—and probably a place you haven’t even yet had a chance to see.

Debar Pond is a small glacial lake in the town of Duane, located in the northern Adirondacks. It is wholly contained within the Debar Mountain Wild Forest, undeveloped except for a small campus of log structures situated along its northern shore. It has been fully opened to the public for about twenty years, but the site is so far off the beaten track (not remote, just isolated from the main population centers of the Adirondack Park) that relatively few people make the effort to see it.

Nevertheless, Debar Pond and its associated buildings are the subject of what might soon become the next amendment to Article XIV, the “forever wild clause” to the New York State constitution that has made the Forest Preserve uniquely protected since 1894. The impetus for the amendment is not to settle a title dispute or preserve municipal access to a water source, but to solely give control of the vacant buildings to an ad-hoc committee intent on their preservation.

Debar Lodge

Why these buildings? Presumably because of their historic merit—though you could be forgiven if you’ve never heard of Debar Lodge before. George Washington never staged a battle from this location, nor did Florence Nightingale nurse anyone back to health. The site is believed to be historic not because of what happened at the pond, but because of the money that was spent: wealthy landowners from out of state hired an esteemed architect to design a log camp in a style derivative of what had already been prevalent for half a century.

Debar Lodge is described by proponents as “one of the largest full-log buildings in the Adirondacks… reminiscent of the great lodges of the National Parks of the American West.” It was built in 1940 as a private camp owned by a couple from Palm Beach, Florida. The architect was William Distin, based in Saranac Lake.

The main building is set amid mature pines about fifty yards from its namesake pond—and within view also of its namesake mountain. Nearby stand a moldering collection of attendant structures, including a caretaker’s cottage, a horse barn with a collapsed roof, a greenhouse, and other odds and ends.

This would have been just one of a thousand such camps throughout the Adirondack Park—unknown to both conservationists and historic preservationists—had the land on which it stands not been sold to the state for inclusion in the Forest Preserve in 1979. The buildings themselves were subject to a 25-year exclusive use agreement, which expired in 2004. They have been essentially vacant ever since.

For the last two decades, then, the lodge and its outbuildings have been “non-conforming structures,” the troubling label applied to any man-made structure standing in contradiction to Article XIV, which allows no structures in the preserve other than lean-tos and such.

Article XIV provides the strongest protections for any public land in the United States, more ironclad than anything overseen by the National Park Service (witness, for example, the back-and-forth presidential declarations regarding the Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments in Utah). The process of amending the state constitution is designed to be taken seriously, requiring the approval of two consecutive sessions of the state legislature followed by a vote of the citizens of New York.

It is also said that Article XIV amendments are supposed to be rare, which in turn makes them relatively safe. But no other section of the state’s constitution is presented to the voters for amendment as frequently as “forever wild.” We hardly ever get to weigh in on the balance of power in Albany or term limits for its power brokers, for instance, but changes to Article XIV are put to a vote several times every decade—more frequently than voters are asked to fill our two U.S. Senate seats.

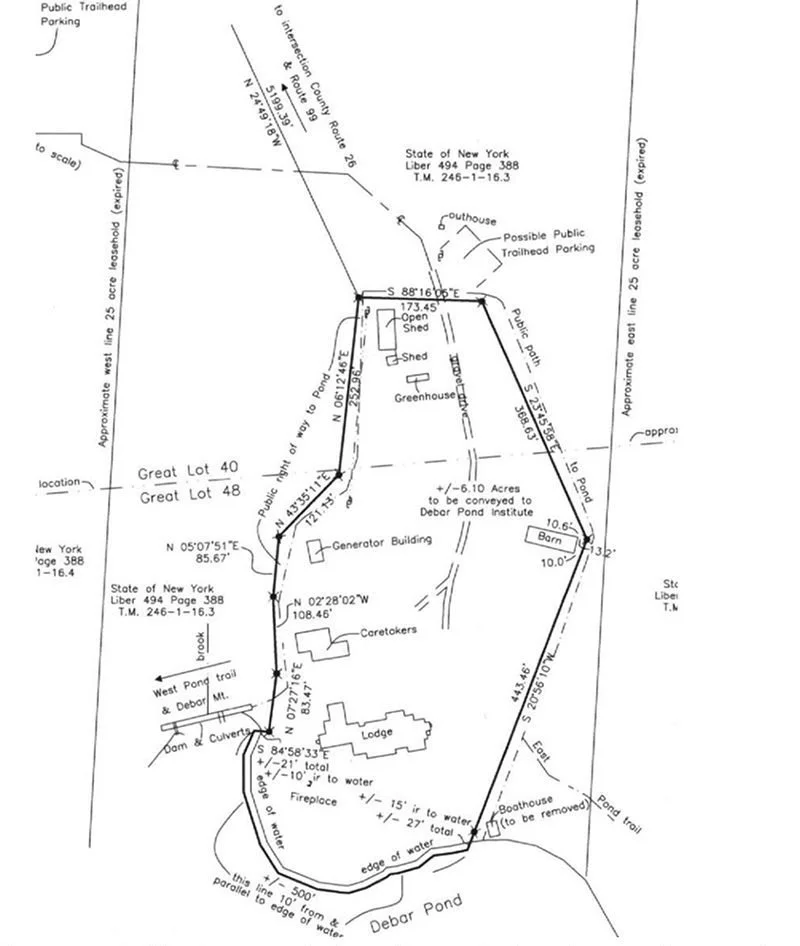

The amendment currently under consideration would remove about 6.1 acres of land along the shore from the Forest Preserve, in an oddly-shaped polyhedron that naturally envelops all of the primary buildings. The newly-formed Debar Pond Institute promises to preserve these structures for their historic value, in exchange for at least 300 acres of “new” Forest Preserve land—although where that new acreage lies has been less forthrightly disclosed.

Baseline Criteria for Article XIV Amendments

How does one objectively measure the merit of a proposed Article XIV amendment? If your priority is to maximize the health and value of the Forest Preserve, then establishing baseline criteria should be the first step. Proposed new amendments are often compared to prior ones, as though past performance is a predictor of current merit. But this is not always helpful because some measures that did succeed in past decades might not survive if they were to be re-tested today. Just because something similar happened one or two generations ago doesn’t mean voters are obligated to repeat those decisions.

In regards to Article XIV amendments, every proposal begins with the contemplated alienation of public property—specifically, some contested piece of the Forest Preserve. Therefore if we were to establish baseline criteria for considering whether the proposal had merit from a wilderness preservation perspective, the very first test might read like this:

The primary motivation for subtracting or encumbering acreage from the Forest Preserve must be to provide a public benefit.

Any good proposal will begin from a need to fulfill a public good—even if this good is only realized at a local level. And there have been many good examples of this throughout the history of the Adirondack Park: establishing cemetery boundaries, preserving municipal water rights, resolving disputed land titles, and allowing for safer highways.

On the other hand, proposed exchanges that are motivated by private concerns should be greeted more skeptically. The recent experience with the NYCO Amendment, which passed narrowly in 2013, should still be causing sleepless nights for those conservationists who apostatized themselves by supporting it.

The result of the constitutional action must also provide a net benefit to the Forest Preserve, meaning not only the receipt of an equal or greater amount of acreage, but also acreage of equal or greater value, when compared to the acreage that has been subtracted or encumbered.

The second test states that not only should there be a clear public benefit for subtracting land from the Forest Preserve, but that there should be a reciprocal action that makes the public land better—and not simply bigger—than it was before.

Debar Mountain above Debar Pond

When these two simple tests are applied to considering whether trading away the 6.1 acres of state land at Debar Pond is a wise decision, the discussion becomes reframed as follows:

Why does the public need these buildings? What public service is gained by taking the structures out of the Forest Preserve? Is public interest in the buildings sustainable?

Who is the Debar Pond Institute, our would-be trading partner, and what is their track record? Do they have the funding an experience to maintain a campus of aging log structures over the course of years and decades? What happens if the Institute fails?

Does the Institute own the minimum 300 acres of land pledged in exchange for Debar Lodge? Is this new acreage of equal or greater value compared to the 6.1 acres at Debar Pond? What value does it provide to the Forest Preserve, aside from bulk acreage?

Note that several of these questions may seem deceptively simple. However, at the heart of this proposal is an action that would effectively give 6.1 acres of prime waterfront real estate to a private entity. While the focus of the proposal has been the alleged value of the lodge’s architectural style—more on that later—no one has mentioned the sheer economic value of the parcel.

So does this mean the Debar Pond Institute will acquire on the people’s behalf 300 or 400 acres of waterfront property in exchange for the lodge site? Some media reports in 2023 affirmed that yes, the new land will be located on Meacham Lake—without bothering to consult a map, which would’ve shown that Meacham Lake is already fully-owned by New York State.

If all we received in exchange for Debar were random plots of forest totaling 300 or 400 acres, in places of little recreational or environmental value, what would that really accomplish for the Forest Preserve?

The Price for Preserving Empty Buildings

Thus the merits of this proposed amendment begin to collapse under the meekest of analytical scrutiny, due to the fact that some of the most important questions we should be asking can’t be answered until after a decision is made.

Let’s start with the first question: How does the public benefit from saving these buildings?

Before getting carried away with debating the supposed historical merit of the buildings, let’s not forget the public would be losing something exceptional: an easy-to-access recreational site with no scenic parallels in this secluded corner of the Adirondack Park. Make no mistake, the 6.1 acres desired by the Institute include the entirety of the developed site, including the sloping lawn with stunning mountain views that enchants all visitors. Instead, public access would be reduced to two peripheral rights of way leading literally into the shoreline weeds.

The buildings and the 6.1 acres would not be open to the public, aside from once-a-week tours in the summer (implying the hiring of staff, ongoing funding, and sustained public interest). Otherwise this would be a conference center or vacation rental—whichever generates the revenue.

Proposed Debar Lodge Project Map

So if you have not been to Debar to see the property personally, take this advice: Go now! The vista from the northern shore—and specifically from the lawn directly in front of the main lodge—is indeed spectacular. This is not just another pretty Adirondack lake; indeed, there’s nothing else in the immediate neighborhood like it. The Debar Mountain Wild Forest is known for its glacial landscape and sometimes monotonous pine forests. But here is a wild little pond surrounded on three sides by rugged mountains: lofty Debar, aptly-named Baldface, and distant Loon Lake Mountain.

Dave Gibson of Adirondack Wild has described this setting as “Fjord-like,” and he’s right. The vertical rise of close-flanking Baldface and Debar Mountains is prodigious; Debar Mountain rises nearly as high as Henderson Mountain above Henderson Lake, and not much less than Blue Mountain towers above its own namesake lake. The pond’s narrow profile and curving shoreline promises unexplored mysteries for anyone who comes armed with canoe paddles. It is a sublimely wild view; the feel of wilderness is broken only by the lodge and outbuildings, which are currently unused, vacant, and immaterial to the outdoor experience.

But the quality of this view requires alignment with the lodge, and it diminishes when the observer moves to either the right or left. If the Institute got its way, the nearest point of public access would be about where the collapsed boathouse is now, practically in the alders. In other words, there are no 400 acres anywhere in the vicinity capable of recreating what these 6.1 at Debar Pond accomplish so breezily.

Aligned View of Debar Pond

Some observers, including PROTECT Executive Director Peter Bauer, have made comparisons between Debar Pond and Lake Lila, a pristine wilderness lake that benefitted from the removal of a Great Camp when the state acquired the land in the 1970s. It’s a useful comparison, although Lake Lila is more remote. Debar Pond’s parking area is less than 5 miles from a main state highway, only 0.7 mile from the nearest paved county road, and a mere 0.3 mile from the current public parking area. Except for its out-of-the-way location, the site could not be easier to access.

Innovations and Imitations

Still, we haven’t answered why we might need to preserve these buildings—the question upon which all others hinge.

Debar Lodge is certainly large, but in its current state it is boarded up and difficult to assess from the outside. The main structure certainly shows signs of wear and tear, including one portion of the roof that was reinforced before it could collapse upon a lower roof. Certainly all of this is salvageable, but that’s not the primary question: would the effort be worth the significant disruption to the public’s right and ability to enjoy public property?

We are no architectural experts, and we make no such pretensions. And yet it would take an architectural expert to appreciate the lodge’s mediocre claim to historical status. The lodge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014, yes, but its selection was based on purely aesthetic criteria and does not mandate the structure’s preservation above all other priorities.

Debar Lodge

Walking around the boarded-up structure, one can see nothing whatsoever unique about the place from a purely architectural perspective. If you need convincing, then take a long drive through the Adirondack Park—any highway, any time of the year. No matter where you go, you are guaranteed to see dozens of similar log camps, of varying sizes and conditions, including many new ones under construction.

Debar Lodge is no Great Camp. Its construction surely pleased Mr. Distin’s paying clients; the Floridians no doubt requested a specific style, and received what they paid for—identical to the way plans for expensive vacation homes are drawn up today. But the lodge was afterwards forgotten by the outside world until threatened with removal.

No one should make the mistake of confusing Debar with bona fide Great Camps like Sagamore and Uncas. These famous buildings are truly historic because they were innovations, elevating humble building materials into grand Gilded Age designs in ways that had never been seen before. They were inhabited by the Brahmins of their time—people with names that remain recognizable more than a century later.

What came after the Great Camps, though, were no longer innovations but imitations. Less-fabulously rich people saw what the Vanderbilts were having and wanted a smaller version of Camp Sagamore to call their own, in a process that has continued uninterrupted into the 2020s, funded by the up-and-down vicissitudes of the national economy and influenced by trends in the regional real estate market. If these Less Great Camps say anything at all about Adirondack culture, be assured it has little to do with the various techniques for joining logs.

Sure, anyone would savor an opportunity to sit on Debar Lodge’s restored porch and take in that vista, but remember that if the Institute gets its way, anyone would no longer be invited to do so.

Former Boundary Line at Debar Lodge

Not a Zero Sum Game

As of December 2023, the amendment to save the lodge has achieved first passage in the New York State Assembly but has not yet been acted upon by the Senate, therefore it remains several steps from adoption. Nevertheless, this is an active proposal that may still find its way to ballots in some future November.

Adirondack Wilderness Advocates has recently decided not to support the amendment, in favor of preserving the natural beauty of Debar Pond—in our view, the one truly unique resource worthy of protection here.

But is this really a zero-sum game? Historical preservationists have implied that if Debar Lodge isn’t preserved in its current location, then it will be destroyed—providing the impetus to act now before all is lost. The unspoken alternative, of course, is that the buildings could be relocated to a less controversial site. Thus they would continue to provide value, as would the 6.1 acres of Forest Preserve at Debar Pond—both allowed to exist, but just not in the same space.

As for Debar Pond, any solution that infringes on public access is not desirable. Rather than being a place from which the public has been excluded, this should become a hub for human contact with mountains and water. The lodge site should remain open to everyone. Few locations in the Debar Mountain Wild Forest are better suited for accommodating such a wide spectrum of users, from those with mobility impairments to those seeking mountain trails and a place to paddle. While preserving the lodge wouldn’t completely prevent public access, it certainly would limit it—as outlined in the plan drawing showing the proposed new boundaries.

Debar Pond is a rare and precious resource, and it must be treated as such. There are many fine lodges in the Adirondack Park—some of significant historical value, others less so—but there are far fewer wild, motorless bodies of water on par with the sheer scenic value of this one. Reversing Debar Pond’s legal protections to save these specific buildings is unjustifiable, as it would remove the most spectacular portion of the pond’s shoreline from the public’s reach without accomplishing any significant public benefits.

Debar Pond in its entirety should and must remain Forever Wild. Join AWA and tell your legislators to vote no and keep Debar Pond forever wild.