A Brief History of the Pepperbox Wilderness

The Pepperbox Wilderness occupies a little-known corner of the western Adirondacks, a place with few official facilities and some of the lowest visitation levels in the park. Those who have taken the time to acquaint themselves with the Pepperbox may be true connoisseurs of wilderness; they have come to know its quiet ponds, its tannic streams, and its labyrinthine fens as personal friends, delighting in their subtle changes as they explore the area season after season, decade after decade.

If the Pepperbox seems far beyond the part of the Adirondack Park known to most people, this has not always been the case. Like any other portion of the Forest Preserve, there is a human story hidden in the second-growth forest, and in the odd place names that lie scattered across the map. This may have been a true wilderness when sportsmen, lumbermen, and land speculators first set foot here, and it may be true wilderness now, but the brief detour it took between these time periods is also remarkable in its own way.

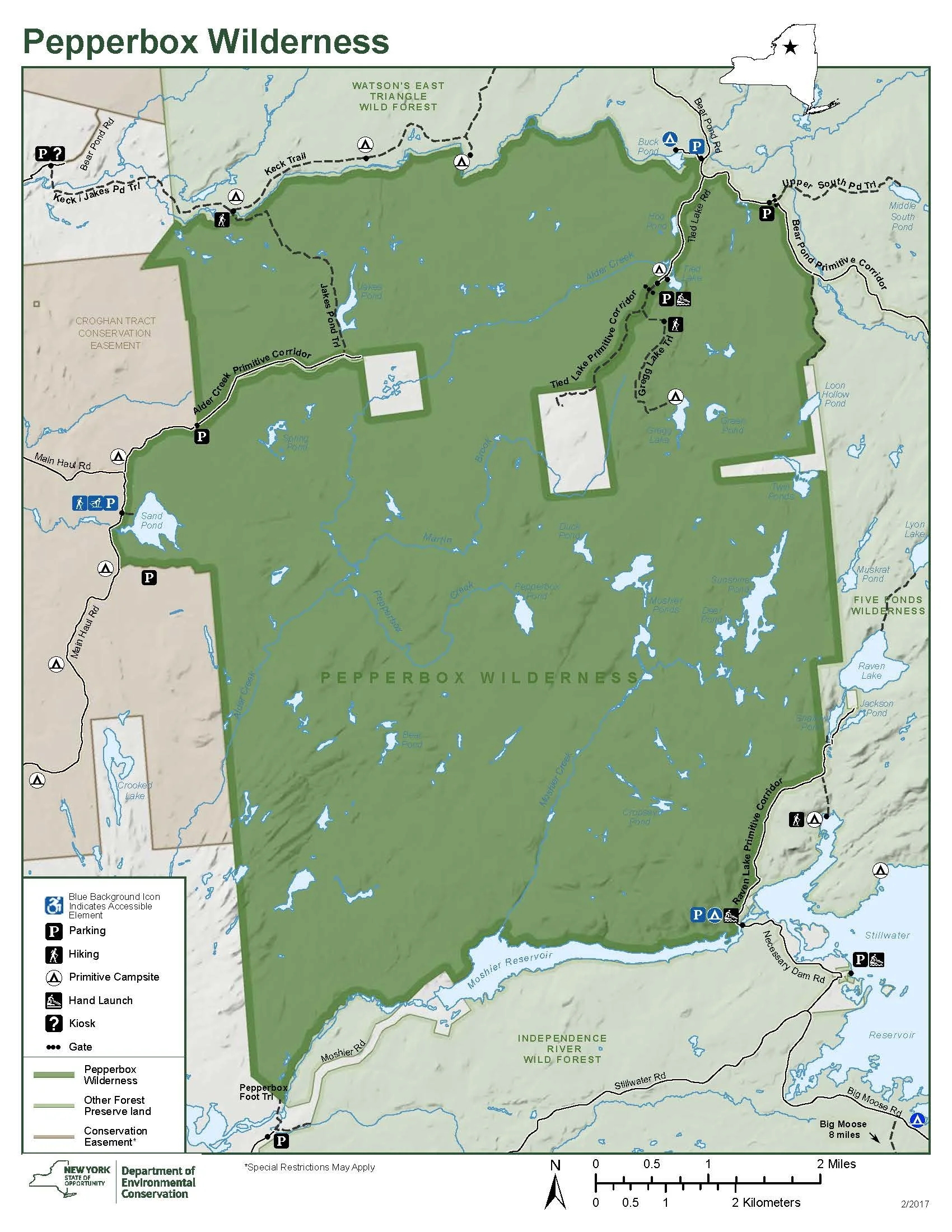

Map of the Pepperbox Wilderness

Despite its modern reputation, the area had probably never been trailless, at least not after the Emilyville Road was chartered by the state legislature in 1814. One of the petitioners was James Watson, who owned two large triangular tracts along the course of the proposed road, and who also became one of the commissioners in charge of its completion. The general route of the road led from Turin in central Lewis County “to the township number fifteen in Macomb’s purchase, commonly called Emilyville,” referring to a small tract along the southern boundary of St. Lawrence County.

The southern half of the Emilyville Road probably followed a medley of existing roads through the Black River Valley, and then a new route along Burnt Creek to the settlement at Number Four. This latter section roughly paralleled modern Number Four Road, but it was located a short distance to the south of the paved highway now traveled by automobiles.

The section north of the Beaver River, however, traveled through what was then—and remains today—a wild and unsettled country. Its exact route is not known, but it likely followed a northeasterly course through what are now the Pepperbox and Five Ponds wilderness areas. It may have passed near Alder Creek and Hog Pond in the Pepperbox, as well as Rock Lake, Wolf Pond, and the Five Ponds in the Five Ponds Wilderness.

Its northern terminus in “Emilyville” was a junction with the old Albany Road, midway between the Oswegatchie Plains and the site of today’s Inlet canoe landing on the East Branch Oswegatchie River. Its urbane name aside, the Emilyville township was (and still is) a largely uninhabited tract. Nineteenth-century guidebook writer Edwin R. Wallace noted that the Emilyville Road “proved a failure; as this wild highway was never much traveled, and soon fell into total disuse. Now thrifty second growth trees and occasional patches of corduroy, obscurely mark its course.”

If the road failed to attract settlers to the Pepperbox region, the ponds and deer herds did capture the attention of sportsmen. Wallace’s annual guidebooks to the Adirondacks listed quite a few trails to the interior ponds, including what were then called Jake’s Pond, Grigg’s Lake, and “Tide Lake,” so named because of its “phenomenal rising and falling water.” Like many other parts of the Adirondack wilderness, the Pepperbox was bounded by several small hotels and lodges: Fenton’s at Number Four, and the Bald Mountain House where Camp Oswegatchie now stands. Paths, woods roads, and even a “hay road” connected the tourist centers to the hidden places where the trout resided. According to lore, when someone found a box of pepper hanging beside one of the ponds, they named the place Pepperbox Pond accordingly.

Jakes Pond

An 1890 map of the Adirondack forest showed the Pepperbox region as being uncut and unburned at that time—a virgin forest. Much of this land was originally part of the northernmost reaches of John Brown’s Tract, the sprawling eighteenth-century land purchase named for its reluctant Rhode Island owner. Large portions of that tract were later purchased by Lyman R. Lyon, a member of the mill-owning family for which Lyons Falls was named. Upon his death, Lyon bequeathed his landholdings to his daughters: Julia Lyon deCamp received a generous amount of acreage around modern Thendara, including much of what is now the Ha-de-ron-dah Wilderness, and Mary Lyon Fisher took ownership of a large tract to the north near Number Four.

In 1906 and 1908, Mrs. Fisher engaged in two separate-but-concurrent logging contracts for softwoods and hardwoods that would have apparently resulted in a vast clear cut. The state’s Forest Preserve purchasing board attempted to seize the Fisher land through condemnation proceedings in 1909 to prevent the clearing of these 23,000 acres. It was a simple process: the board members passed a resolution condemning the land, and obtained the oral consent of Governor Charles Evan Hughes. However, the state comptroller objected to those proceedings and refused to issue a payment to the Fishers. This touched off a legal dispute that would not be resolved until 1922. During this time New York State claimed ownership of the land for the Forest Preserve, but because no compensation was issued the courts eventually invalidated the state’s claim and returned the land to the Fishers.

By this time Mrs. Fisher’s son, Clarence Fisher, had become the primary steward. With his sister as a business partner, he set up the Fisher Forestry & Realty Company to manage the land and sell off small building lots. Clarence had a keen interest in modern forestry practices, and as a member of the state legislature he sponsored (and passed) the Fisher Forest Act.

According to a historical sketch provided in the 1985 unit management plan for the Pepperbox, logging did occur from the 1890s through to the 1920s, and notable forest fires did singe the edges of the area. However, despite the state’s concerns at the time, it was likely that the Fishers targeted only the softwoods. Woodsmen used tote roads to access the interior camps at places like Bear Pond and Cowboy Beaver Meadow, but the logs were flushed out of the woods along the area’s natural highways: streams such as Moshier, Alder, Martin, and Pepperbox, all of which fed into the Beaver River.

Clarence Fisher was also a trustee for the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, and he served on the board of governors for the Adirondack Mountain Club. These affiliations may have inspired him to later become a willing seller to the state, because in 1932 Fisher Forestry began to sell large blocks of land to the Forest Preserve, including what later became the Pepperbox Wilderness and the Independence River Wild Forest—some of the same lands that had been unsuccessfully condemned in 1909.

At the time the Pepperbox Wilderness was first designated in 1972 it consisted of 14,600 acres between the Beaver River and the southern line of Watson’s East Triangle—all of it purchased in 1932 from Fisher Forestry, except for a couple 1877 tax sale lots on the north end. But it was not a trailless area. The 1972 State Land Master Plan (SLMP) listed the presence of a 1.5-mile foot trail and a 0.5-mile jeep trail, both of which presumably led to what was called the “Beaver Lake Mountain” fire tower. This structure, built in 1919, stood on an unnamed rocky ridge north of Threemile Beaver Meadow. It was refurbished after the 1950 hurricane swept through the Adirondacks, but it was apparently not a popular hike. The SLMP said there was “little or no demand for a trail system, and this offers an opportunity to retain a portion of the Adirondack landscape in a state that even a purist might call wilderness.” State employees removed the fire tower and observer’s cabin in 1977, and the ridge that it stood upon sank once again into nameless obscurity.

Threemile Beaver Meadow

The Pepperbox Wilderness UMP was issued in March 1985, making it one of the first completed plans for any part of the Adirondack Forest Preserve. Prior to that year, DEC had been encountering significant knowledge and staffing setbacks in regards to management planning. The Pepperbox was probably completed so early because as a wilderness with no facilities, it was considered to be “low-hanging fruit.” By then there really was minimal public interest in exploring the area; the ponds were mostly fishless victims of acid rain, and the Pepperbox’s busiest season was October and November, when a handful of hunting parties applied for camping permits. The only state facilities were located on the periphery of the wilderness to provide access to its southern boundaries.

The state acquired much of the Watsons East Triangle area to the north of the Pepperbox in 1986, leaving a string of small inholdings along the triangle’s southern line like the perforated edge of a postage stamp. (One of these inholdings had been acquired by employees of the previous owner, International Paper.) Then in 1999 more land was sold to the state, including two of the Watsons East inholdings.

Thus the predominant land use in the region became wilderness preservation, with a consolidated Forest Preserve interspersed with a few private hunting camps and their related access roads. These land acquisitions allowed the state to expand the boundaries of the Pepperbox Wilderness northward to the West Branch Oswegatchie River in 2000, and into Lewis County a few years later.

Older versions of the SLMP described the Pepperbox as “heavily burned over and logged in the past and … not particularly scenic by usual standards,” but this appears to be an overstatement unsupported by observation and experience. The area is consistently forested with second-growth hardwood and softwood stands today. It is far from virgin, but hardly denuded, either.

As you visit the area in the twenty-first century, a woodpecker may drill loudly into the upper reaches of a maple tree, the mellow knock-knock-knock-knock-knock wafting through the forest more like a balsamic scent than a sound. The ice of some remote little pond may groan and pop overnight under the pressure of a surprise March cold snap, swiftly reversing a day’s worth of thawing. And in the spring, a swollen creek may roil through the confines of a hidden gorge, the existence of which you never suspected until you stumbled across it on a search for something else.

When these things happen as you explore and enjoy the Pepperbox, nothing could be more right with the world.

Site-Specific Histories within the Pepperbox Wilderness

Although the Pepperbox Wilderness is little-known today, the names of its various features have been in place for many years. References such as the guidebooks of Edwin R. Wallace suggest explanations for how these landmarks were named, although there is no way to confirm these claims.

Bear Pond. Referring to the small pond near Threemile Beaver meadow, Wallace also called it Cold Lake and stated one could get there by trail from Gregg Lake. (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 120.) Murphy’s Camp was located here, from which the last logging operations were conducted. (Pepperbox UMP, 1985, p. 3.)

Beaver Lake Mountain. The state erected a log fire observation tower here in 1910, and replaced it with a steel structure in 1919. However, because of redundancies with other nearby towers, it was closed in 1945. Despite a brief resurgence of interest after the windstorm of 1950, the Beaver Lake Mountain tower was closed permanently in the mid-fifties, and removed in 1977. (Podskoch, 2003, pp. 58-59.) This may have been the site of the “Duvlin Hills,” where a lumber camp once stood. (Pepperbox UMP, 1985, p. 2.) The name “Beaver Lake Mountain” was apparently invented by the Conservation Department for the benefit of the fire tower, as the ridge upon which the tower stood has never had an official name. That said, the “mountain” consists of an interesting band of parallel ridges—one of the most interesting land features in the Pepperbox Wilderness. The tower site has no natural views, but open ledges can be found on other parts of the ridge.

Cowboy Beaver Meadow. This name is not explained, but its location on Alder Creek matches the location of Wallace’s Seven Mile Meadow, which could be reached by hay road (possibly a surviving section of the Emilyville Road) or blazed line. It was reportedly “a favorite resort of the angler.” (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 98.) A lumber camp stood here, at the confluence of Pepperbox Creek and Alder Creek. (Pepperbox UMP, 1985, p. 2.)

Crooked Lake. This privately-owned body of water is not within the Pepperbox Wilderness, but Wallace gives it special mention. He described it as unattractive “as far as beauty of surroundings is concerned,” but it was known as a quality trout fishery. The alternate name was Lake Agan, in honor of Patrick H. Agan, Esq., of Syracuse, who frequently fished here. Wallace credits Mr. Agan as a father of the movement “to preserve the Adirondack Wilderness from the hands of the spoiler,” further noting that he was once a “confirmed invalid” cured by “this health-restoring region.” (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 96.)

Gregg Lake. Wallace spelled the name of this lake as “Grigg’s Lake.” (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 120.) New York State acquired the lake from Champion International and designated the first marked hiking trail here in 1999. (DEC, “Croghan Tract” pamphlet, 1999.) In 2015, the state tabled a plan to build a lean-to at Gregg Lake. Instead, it designated a campsite and a second marked hiking trail—denying that the first trail ever existed. (DEC, UMP Amendment, 2015, pp. 8, 12.)

Hog Pond. This was named for a group of hogs that escaped from a pen at one lumber camp near Alder Creek and took shelter in the root cellar of the logging camp located here. (McMartin and Ingersoll, 2007, p. 75.)

Jakes Pond. According to Wallace, this was named for a “famous woodsman.” The trail from Long Pond Road passed “a remarkable natural rock camp,” and a hunter named “Uncle Bill” Lawrence kept a solitary camp near its shores. (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 119.)

Martin Brook. Within the Pepperbox, the largest section of blowdown caused by the 1950 hurricane occurred here. Salvage operations were conducted along the course of a “Blowdown Road” that traversed the area roughly from Spring Pond to Gregg Lake. (Pepperbox UMP, 1985, p. 4.)

Moshier Ponds. Per Wallace, these were “named after their discoverer, the distinguished sportsman residing in Lowville.” Trails led there from Crooked Lake, Number Four, and Gregg Lake. “Their warm and shallow waters contain no trout.” (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, pp. 99, 120.) A lumber camp stood at the lower pond around the turn of the twentieth century, and logs were floated down Moshier Creek to the Beaver River. (Pepperbox UMP, 1985, pp. 2-3.)

Pepperbox Pond. According to lore, this pond was named when someone found an old can of black pepper wired to a tree along the outlet. (McMartin and Ingersoll, 2007, p. 43.) Except for modern publications recounting this story, no source documents have been found. The name was already in use by the time Wallace began publishing his guidebooks.

Sand Pond. This pond was known to Wallace as Sand Lake. It was “a favorite locality for deer hunting,” but it had no trout. (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, pp. 96, 98.)

Sunshine Pond. This may be the “100 Acre Pond” that Wallace mentioned was located close to the Moshier Ponds. Sunshine is the largest pond within the Pepperbox Wilderness, but by modern measurements its only 64 acres in size. (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 99.) A forest fire burned in this vicinity in 1913. (Pepperbox UMP, 1985, p. 4.)

Tied Lake. Wallace spelled this “Tide Lake” with the explanation that it was known for its “phenomenal rising and falling water.” (Wallace, 14th edition, 1889, p. 120.)

West Branch Oswegatchie River. According to Horatio Gates Spafford in his 1813 Gazetteer of New York State, the Indian River that begins in Lewis County and flows into Black Lake was also once known as the West Branch of the Oswegatchie. Today, that name is applied to a smaller tributary beginning at Buck Pond, forming the northern boundary of the Pepperbox Wilderness. (Spafford, 1813, pp. 214-215, 267)

Sources

Amendment to the 1985 Pepperbox Wilderness Area Unit Management Plan, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, June 2015.

“Croghan Tract/Northern Flow River Area: Adirondack Forest Preserve Map and Guide.” New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, 1999.

Ingersoll, Bill and Barbara McMartin. Discover the Southwestern Adirondacks. Barneveld, New York: Wild River Press, 2013.

McMartin, Barbara and Bill Ingersoll. Discover the Northwestern Adirondacks. Barneveld, New York: Wild River Press, 2007.

Pepperbox Wilderness Area Unit Management Plan, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, March 1985.

Podskoch, Martin. Adirondack Fire Towers, Their History and Lore: The Southern Districts. Fleischmanns, New York: Purple Mountain Press, 2003.

Spafford, Horatio Gates. A Gazetteer of the State of New York. Albany, New York: H. C. Southwick, 1813.

Wallace, Edwin R. Descriptive Guide to the Adirondacks, fourteenth edition. Syracuse, New York: Bible Publishing House, 1889.