Members of the Adirondack Park Agency are experiencing a crisis: some of them confess they don’t know what a road is, or more importantly, how to count them. Of specific concern is this question: if a road leads into a wild forest, is it still a road?

For the last year, these have been recurring topics of discussion during APA meetings. It seems the agency is only now waking to the realization that there may be too many roads in the Adirondack Forest Preserve, and that we need to either (a) perhaps close a few of them, or (b) develop a more liberal counting method.

To be clear, by “roads in the Adirondack Forest Preserve” we don’t mean public highways, which may pass through and around public lands but are legally a separate entity. Rather, this is a question about roads within the Forest Preserve: the ones that came with the land and are owned entirely by the Department of Environmental Conservation. They might be old “fire truck trails” constructed in the 1930s, or private rights of way leading to isolated inholdings, or roads opened by DEC for recreational purposes.

And to be even more specific: at issue are the roads open to motor vehicles within lands classified as Wild Forest.

If this sounds like an old discussion, you are most certainly correct—it goes back as long as there have been motor vehicles capable of penetrating wild spaces. For people who see the intrinsic value in preserving vast tracts of undeveloped nature, nothing is more existentially threatening than the idea of a road winding for miles into the deep backcountry. It turns the remotest areas inside out and diminishes the sensual value of the wilderness experience for those who crave it.

In the Adirondack Park, the issue was thought to be settled in 1972 when the nascent APA issued its first major achievement: the original State Land Master Plan, the celebrated conservation document that sought to limit the amount of acceptable development on our state lands. The SLMP didn’t place an outright ban on roads in the Forest Preserve, but it did try to set benchmark standards against which all future decisions could be measured.

Specifically, the master plan limited roads to roughly half of the Forest Preserve. In the areas designated as Wilderness, roads were explicitly banned—as were nearly all forms of motorized access. This action was necessary to provide areas where people could experience a form of unmitigated nature, where the “imprint” of modern civilization was “substantially unnoticeable.” Where roads did exist within the new Wilderness boundaries, the SLMP required DEC to close them in the most expedient manner, allowing them to revert to natural conditions over time.

The other major state land classification was Wild Forest, which had somewhat more permissive guidelines. Roads and snowmobile trails could continue providing access, but not without a stringent set of guidelines of their own. Of particular note, the SLMP…

- …defined a road, regardless of how it was actually used, as a “way designed for travel by automobiles.”

- …stated DEC may allow the public use of Wild Forest roads, but only on those already in existence.

- …stated no new roads may be constructed.

- …stated “there will not be any material increase in the mileage of roads and snowmobile trails open to motorized use by the public in wild forest areas that conformed to the master plan at the time of its original adoption in 1972.”

If all of these guidelines were illustrated on a traditional Venn diagram, with overlapping circles to flesh out the common themes, they would center our focus upon a simplified mandate that all state land managers could follow. Such a mandate might read like this:

If it’s not designed for automobile use, then it’s not a road—and if it’s not a road, then no one should be driving on it. You can’t make new roads, and the ones added through land acquisition can’t significantly expand the total mileage beyond what it was in 1972. And if you’ve already reached your mileage cap, then every new mile of road opened in one location must be offset by the closure of another mile of road somewhere else.

While this may sound like a straightforward set of management guidelines, the on-the-ground situation has always been somewhat more crooked. For instance, roads can and do exist for any number of reasons on state land: they may be subject to private rights of way, or provide administrative access to key facilities. Some were created by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s to provide emergency access in the event of a forest fire, and others were preexisting structures at the time a parcel of land was added to the Forest Preserve. There is no centralized catalog for every road that needs to be counted and measured.

The question, though, is how many of these remain open today; if a particular road was barricaded long ago and allowed to revert to nature, then no one need worry about counting it. But if DEC has been maintaining the road, or allowing people to use it, then it must be counted toward the parkwide total and weighed against the SLMP’s “no material increase” benchmark.

Granted, the state may have no authority to close some roads across the Forest Preserve, such as those protected by a private landowner’s legal right of way. However, the roads most people care about are those that are used for recreational purposes—the discretionary routes that serve no practical purpose, but provide deep access for those who can’t (or don’t want to) hike long distances.

Since 1972 the state has acquired vast acreages of former timberlands with extensive logging road networks. In each case, APA and DEC have been required by the master plan to make up-front decisions about how these new lands will be managed. Not every new tract resulted in a public controversy, but public controversies are hardly a new development, either. Often the debate zeros in on the status of those logging roads, and whether they should be permanently barricaded or opened to all comers.

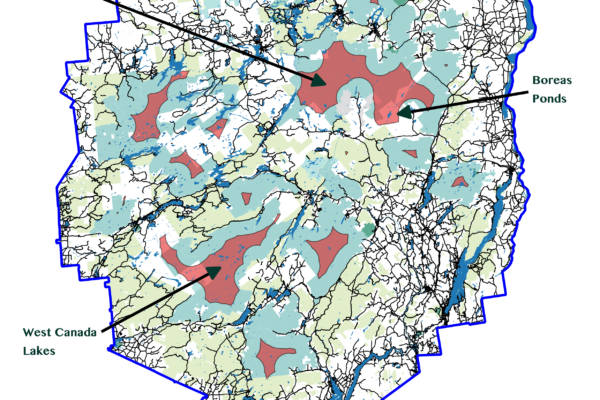

The only way the state could violate its “no material increase” mandate was to open these new roads on these new acquisitions without closing an equal amount of roads elsewhere—and this seems to be the exact pickle the two agencies are facing today. Just a few years after the state insisted on adding dozens of new Wild Forest road miles after the landmark Finch Pruyn purchase, which gifted the outdoor-loving public with such prizes as the Essex Chain of Lakes and Boreas Ponds, APA members are now openly questioning whether they have to count all road miles, or just certain preferential ones.

Sometimes the greatest threats to the integrity of the wilderness are those entities tasked with its preservation.

Sometimes the greatest threats to the integrity of the wilderness are those entities tasked with its preservation. Unfortunately this is not a new phenomenon either, but it is dispiriting to see the process play out once more. Currently the APA board is packed with people disinclined to see wilderness protection as a priority—who probably even see it as a threat to economic vitality, broadly conceived as “people doing things with a monetary value.” Closing off vast tracts of forest to most forms of motorized access is the precise outcome they come to Ray Brook hoping to prevent.

The other half of the board presents itself as a younger constituency, one that perhaps aspires to the institutional memory the APA recently possessed (prior to staff departures and retirements) but lacks the wherewithal to counter the pro-motor contingency. What does “no material increase” mean, anyway? And does the use of a Wild Forest road drive its management? Solutions worked out by diligent staffers in the 1970s have devolved into questions for the 2020s, posed in reverse order as though we were all trapped in a half-century gameshow hosted by Alex Trebek.

But seriously, these are the two questions the agency has been stuck on for more than a year. Upon discovering we have too many road miles in the Wild Forests of the Adirondack Park, the APA did not rush into action by dusting off its long-established policies. Instead, its board has been obfuscating the issue by characterizing this as a computational conundrum: what to count and how to count it.

In 2022 the APA board bravely tackled the problem of “no material increase” by pitching the idea that a 15% increase in road mileage in fifty years was “immaterial.” The agency posed this question straight-faced to the public… against the backdrop of an 8.5% national inflation rate, the highest anyone had seen in decades—and certainly no one was calling that immaterial. As a result, the agency’s new road theory was not as warmly embraced as had been hoped.

Establishing the “no material increase” precept at 15% (or more!) would have forgiven a whole lot of road-creep into the Forest Preserve without anyone having to effect any closures, thus solving the state’s conundrum through the power of basic mathematics. But if changing how we count road miles in the Adirondacks was not going to work, perhaps we could pick and choose which roads we wanted to count.

Enter the “Galusha Decision,” a common reference to a 2001 legal ruling that has greatly impacted the way New York State accommodates the needs of those Forest Preserve users who cannot hike. The litigants in that case were disabled individuals suing for motorized access to state lands, and for them the results were mostly favorable. The landmark decision was based on the observation that DEC personnel were using certain roads on state land that were otherwise closed to the general public—and if the department possessed that discretionary power, what prevented it from opening these same roads to people with disabilities?

Notably, though, Galusha changed no laws and overrode no provisions of the SLMP. The state was not obligated to open all gates and allow motorized access everywhere. Instead, the decision named some low-hanging fruit in the Moose River Plains and elsewhere, and stated that additional access opportunities might be identified through routine management planning for the Forest Preserve. No roads need be opened in violation of SLMP guidelines.

In this way, Galusha expanded our thinking about existing Forest Preserve policies without radically rewriting them. One example was Great Camp Santanoni, accessed by a well-maintained gravel road used frequently by state employees but closed to the general public. If this established way was opened to qualified individuals, what could possibly be the harm?

DEC implemented much of the Galusha Decision through its CP-3 permit program (with CP standing for “Commissioner’s Policy”). The department has designated numerous routes in the Forest Preserve as roads closed to the public-at-large, but available to CP-3 permit holders—thus granting people who cannot hike access to a variety of interior destinations. After nearly a quarter-century of implementation, this is a policy that has not run afoul of anyone.

The idea, though, was that these CP-3 routes all had to be existing ways—roads designed for automobile use as sanctioned by the SLMP. Galusha granted no authority to build new roads or exceed any management guidelines. The assumption was that when it came to “no material increase,” these were roads that had already been counted toward the mileage cap. It wasn’t debated because everyone involved at the time understood this to be the intent.

Nevertheless, this is precisely what the APA board is framing as an open question in 2023. Does all that “no material increase” malarkey only apply to roads opened to the general public? Because if that were really the case, then it turns out we have mileage to spare—problem solved! But when we add in all the CP-3 routes, that’s when we tip the scales.

Note the deliberate framing of the problem: that if we insist on leaning into “no material increase,” it’s the routes dedicated to disabled access that are the most vulnerable, the first to be cut. Because they’re the ones that apparently cause the problem.

Bullshit.

There are multiple ways to satisfy the SLMP’s Wild Forest mileage guidelines, and most of them involve doing what APA and DEC should’ve been doing for the last fifty years: culling those roads that provide the least value, allowing natural forces to have their way with them. And these will almost certainly not be the CP-3 routes, which taken as a whole provide an indisputable value to a constituency with few other options.

From where I sit the only real problem is the obstinacy of the two agencies in charge of managing the Forest Preserve. The APA, specifically, seems hell-bent on pitching these manufactured crises to the public, framing the debate in Us-vs.-Them terminology. But these so-called questions are so absurd it is difficult to take the agency asking them seriously; if this were written on a quiz, the students would be justified in suspecting a trick question.

Only one answer satisfies the agency’s latest question, to which responses are due by April 15, 2023:

A road is a road, no matter how you count it.

APA, please stop wasting the taxpayers’ money. Please just admit your past mistakes, and cease these endless flaky daydreams. You’ve been entrusted to do a single job, so stop procrastinating and simply do it.

2 Comments.

[…] In response to these State actions, AWA will be launching a remoteness campaign in three parts. First, we are submitting a proposal to the APA calling upon it to develop a formal policy on remoteness that can measure and better protect it. Second, AWA is organizing a call to action to oppose any attempt by the APA to exceed the road mileage in Wild Forest that is allowed by the SLMP. This has been a long-term problem with the APA, and the current NMI alternatives will make the problem worse, as AWA Vice-Chair Bill Ingersoll explained in a recent essay. […]

[…] Bill’s recent blog post: “A Road is a Road–Any Questions?” […]