Wilderness in the Presence of History

The legal definition of wilderness in the Adirondack Park, since 1972, has in part read “an area of state land or water having a primeval character … [which] generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.” For some people, this sets the expectation that an area so designated is entirely natural and exists just as it did before Homo sapiens ever set foot in North America.

Of course, few places on the planet could ever clear such a high bar, including the deepest recesses of the Adirondack Park. Most of what is now the Forest Preserve is, without a doubt, an exceptionally-preserved piece of nature, but at the same time there is often a human story embedded in the landscape.

And in a few instances, that story is writ large.

It’s the natural aspects of the wilderness that has been drawing me for more than a quarter-century, but I do love me a good paradox now and then – an exception that blurs the distinction between wild nature and human history. They remind me that nothing is ever “black and white,” and never does one element exist at the total expense of the other. Truth, like nature, is neither static nor monolithic – one of the lessons my wilderness experiences have taught me over the years.

I can think of no place where this paradox is more evident than at Sagamore Lake in Hamilton County, where legally-protected wilderness exists in the presence of history.

Sagamore Lake, as most people know, is the site of Great Camp Sagamore, one of the most celebrated examples of regional architecture. William West Durant bought the lake in 1888, when it was still known as “Shedd Lake.” He built his masterpiece in 1895, and sold it (along with 1526 acres of surrounding forest) to Alfred G. Vanderbilt in 1901. This made Vanderbilt neighbors with J. P. Morgan, who owned another Durant accomplishment, Camp Uncas, a few miles away on Mohegan Lake.

Sagamore. Uncas. Mohegan. These are all names from Fenimore’s Last of the Mohicans, the Romantic work of fiction that nevertheless helped inform the popular concept of wilderness for much of the nineteenth century (in ways that modern movie adaptations have failed to reproduce). It seems unlikely, then, that the Vanderbilt family came to Camp Sagamore just to experience untamed nature on its own terms; there were cultural pre-conceptions that needed to be indulged, and certain modern conveniences that required accommodation. Indeed, the campus of log buildings famously included a bowling alley, among other luxuries.

It also included its own power plant, which I’ll get to in a moment.

The Vanderbilts owned Sagamore for half a century. In 1954 they sold it to Syracuse University, who logged the surrounding woods before selling everything to the state in 1972 – all but the eight acres encompassing the main camp complex, thus sparing the Adirondack Forest Preserve from too much contradiction. Historic preservationists took over management of the buildings, which otherwise would’ve been at odds with the “forever wild” clause of the state’s constitution. A voter-approved amendment in 1983 allowed a modest boundary adjustment, thus adding some additional buildings to the new historic preserve. Much of the remaining state-owned land became part of the Blue Ridge Wilderness.

Great Camp Sagamore

Lost Brook

John Hoy Monument, where a Vanderbilt employee lost his life

Azaleas at South Inlet

Old Cistern near Camp Sagamore

Trailhead Sign at Sagamore Lake

Dam Ruins on South Inlet

The Old Sagamore Powerhouse

South Inlet

The word “wilderness” can mean many things to many people, although whenever I invoke the term I am usually referring to the official definition. Likewise, “history” is also a word fraught with little biases. For example, Camp Sagamore is hardly the only example of a place where people once dwelled on land now owned by the state. The Forest Preserve is dotted with little cellar holes everywhere: the humble remains where entire families once lived and grew old together. These sites are practically anonymous now, whereas entire books have been written about Sagamore and the other so-called “Great Camps.” Why all the attention devoted to one but not the other? Isn’t it all “history”?

My point is this: we are impressed by ostentatious displays of wealth, and as far as the Gilded Age in the Adirondacks goes, Sagamore is at the top of that pile. These are unique structures, with plenty of echoes to be seen elsewhere but with no exact copies anywhere. In 2005 actor/director Robert De Niro shot a few scenes of The Good Shepherd here, with Angelina Jolie and Matt Damon in tow. Vanderbilts! Great Camps! Hollywood! “History” doesn’t sprout a capital H faster than that.

The physical footprint of Great Camp Sagamore and its collection of service buildings aren’t all contained in that small private preserve; quite a few key features were spread farther afield, including some surprising structures that now stand within the Blue Ridge Wilderness – and yes, there is some outstanding wilderness at Sagamore too, with an attractive trail network to show it off.

This is a place I’ve been visiting for years, most often in winter, although on one recent June weekend I spent a morning enjoying it in all its greenest finery. Trail stewards have been busy over the last decade building out the trail network, installing new bridges and cutting new detours around mud patches. The result is one of the finest networks of nested loops anywhere in the park, all of it well suited for moderate-level day hiking.

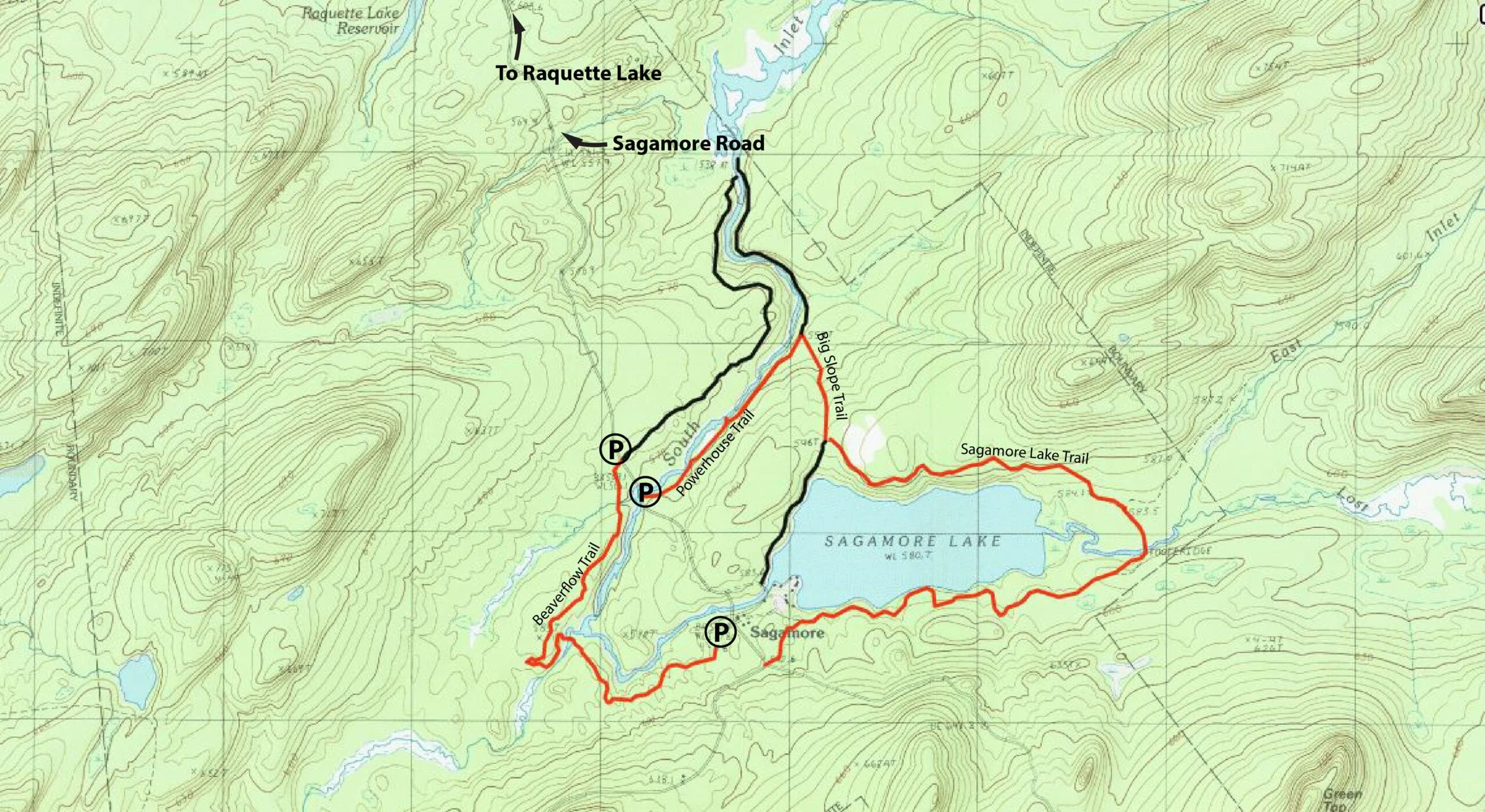

If you want to see as much as possible in a single visit, I’d recommend a 6.5-mile loop that includes not just the trail around the lake, but sections of the Powerhouse and Beaverflow trails as well – the route highlighted in red on the map below.

Map of the Sagamore Loop

Why this route? For one thing, it includes much of the area’s best nature: a brief section of South Inlet, a major stream; the expansive forests of spruce and fir that dominate much of this wilderness, seeming to defy anyone to venture far off-trail; and a stand of tall white pines west of the lake that somehow escaped the woodsman’s saw.

And also the history: not just glimpses of the red-trimmed Camp Sagamore itself, but also a chance to explore – as in physically enter at your own leisure! – the derelict powerhouse where two antique electromagnetic generators can be found inside. Technically such a structure would be deemed incompatible with the wilderness guidelines, but here the effort to demolish such a brick building would do more harm than good, and thus wilderness managers have chosen to let the site be – no preservation, but no active destruction either.

As I said: wilderness in the presence of history.

If You Go

Being a major historical landmark, Great Camp Sagamore is easy enough to find: follow NY 28 to the hamlet of Raquette Lake and turn south on Sagamore Road. Follow it for about 3 miles to the bridge over South Inlet, from which wild azaleas may be spotted in early June (coincidental with the peak of “fly season”). Park just across the bridge on the left, at the start of the Powerhouse Trail. I prefer following this loop in a clockwise circuit, although the terrain itself is agnostic in regards to direction.

To learn more about Great Camp Sagamore itself, including information about guided tours, please see https://www.sagamore.org/.