The Wilderness beyond Mohegan Lake

The snow before us was virginal, and it covered an entire road that extended for several miles into the backcountry. Beyond the mountainous snowbank that marked its beginning, the ribbon of white vanished around a long bend in the woods, with not a track to mar its surface. At another time of the year you might encounter a truck or two bound for one of the cabins at its end, but in winter Bear Pond Road was a forgotten byway, a surplus route orphaned by a society with an overabundance of roads.

“This is what we came for,” I said, and Paul agreed, the conditions looked promising for skiing. We were standing shin deep in fresh powder, no more than a few days old, the result of one of the first good snowfalls of 2019. Beneath the top layer, the old snow from December could be felt under our boots as a crusty base. We had just taken our skis off so we could scramble over the snowbank like a couple of kids, but now the bigger kids inside us were anxious to glide down this wide trail. We hurriedly clipped our skis back onto our feet.

And then we pushed off with our poles, taking long and exaggerated strides. Bear Pond Road began with a long and very gentle descent, with gravity assisting me as I broke trail. We breezed past the almost hidden meadows on the right that once grew produce for the residents of nearby Camp Uncas; and while we were chatting brightly about god-knows-what, we skied right by a big roadside boulder, barely registering its presence.

Above us there was an overarching canopy of tree branches still caked with snow, glistening in the cold sunlight as if the storm had only just cleared out overnight. Higher yet was the dome of blue sky, unbroken and freckled only by a few inconsequential tufts—perhaps the bluest sky we had seen so far this new year. There was a biting chill to the morning; my cheeks were twin frontiers dividing the warmth of my body from the icy air. The snow was dry and faultless. In short, this was January at its finest.

We could tell, though, that the transition from fall to winter had been rough on these woods. The snow had come early this year, but by no means easily; a storm in November had knocked power out across the county, caking the Adirondacks with a doughy layer of wet snow that had become icy and hard the very next night. For many unlucky hunters, deer season was effectively over that weekend, as it was impossible to walk quietly in the woods from that point forward.

Many tree limbs had also come down that month, and the track we were following was littered with fallen debris. Twigs and the butt ends of snapped-off branches reached upward out of the snow, the only imperfections Paul and I could note so far. But since they had been blown out of the treetops so many weeks ago, the recent snowfall had effectively buried them. All we had to do was skirt around some of the larger ones, and to our delight this hardly impaired our skiing.

If these conditions were heavenly, then the first 1.4 miles of our day had been the requisite half-hour of purgatory. When we arrived this morning at the end of Sagamore Road—our two dashboard thermometers in disagreement about the outside temperature, specifically the number of degrees Fahrenheit it was below zero—we were disappointed to see that the caretaker had already plowed the private road past the gate in the direction of Mohegan Lake. The surface hadn’t been scraped to bare gravel; a veneer of hard-packed ice and snow had been left like a layer of frozen pavement. Perhaps this was just fine for an all-wheel-drive Subaru, but it would be almost too marginal for our waxless Fischers.

I had proposed this trip partly on the grounds that these private access roads—one each to camps Uncas and Kill Kare—can be quite fun to ski in the immediate aftermath of a good snowfall. This was not an idle theory I had postulated, but the memory of a good morning I had spent here a few years ago. But whoever maintains these roads had been too efficient this week, and so we would have to scrape by until we reached the turnoff leading around the lake.

That’s not to say we didn’t ski those first 1.4 miles along the private road. With our cars parked opposite the entrance to Great Camp Sagamore, we stepped around the locked gate at the start of Mohegan Lake Road and made the most of an ironic situation: surrounded by the promise of a bright winter’s day, white fluffiness everywhere, but skidding along an icy surface like two bowling balls trying to avoid the gutters on either side of the road’s crowned centerline.

Moonrise over Wakely Mountain

“Are we getting close to Mohegan Lake?” Paul asked as we skied down the unplowed, unused private access road.

I wasn’t quite sure the best way to answer. Indeed, I had promised Paul that we would be skiing to Mohegan Lake, but in reality we were already there—and had been near the lake for several minutes.

“Yeah, it’s right down in that direction,” I said, tipping one ski pole up briefly to the left. “The road is just set too far back to see it.” In my mental map of the area I could see the road arcing around the shoreline at such a distance that it was easy to forget the lake was there. “We’ll have some good views when we get to the other side,” I promised.

I knew of a herd path leading off this road to a scenic campsite on the north shore, and I had hoped to make that a short diversion. However, there was no landmark to indicate its beginning, and in the depth of winter an unmarked trail through an open hardwood forest was practically invisible. When we had passed that big boulder beside the road we had probably been in the right neighborhood; now we were one zip code too far.

Paul offered to take a turn breaking trail, and we continued along the old road flanked by its retinue of second-growth hardwoods. This was not a place that Barbara McMartin would have relished, at least not when I knew her; the road was too obviously a road, and the lumbermen had too thoroughly harvested all of the ancient timber. This was not a whisper of a footpath, winding between spruce trees so tall and thick at the base that even old Sol Carnahan might have blushed in their presence.

The land spoke of its history—a narrative that included someone digging a cellar hole back near the start of the road, and someone else years later placing a folding chair next to a tree, where it now sat rusted and tenantless. We were by no means skiing through an anonymous forest; plenty of people had been here before and left their contribution to the story.

The biggest statements in that narrative were the trio of Great Camps, including Sagamore on its namesake lake, Kill Kare down on Lake Kora, and Uncas here on Mohegan Lake. All three bodies of water had been known by different, less literary names before each had been snatched up by one of the barons of the Gilded Age. And so this land had served time as a private reserve, with a forest that was perhaps viewed as a scenic haven and a cash-generating resource simultaneously.

But as the camps aged and the list of maintenance needs grew longer, ownership changed hands. The new landlords were all well intentioned, but they were less well moneyed than the Vanderbilts and Morgans before them. Scout camps and urban universities both had turns as the stewards of these cultural resources, until the charitable obligation of keeping a Great Camp from crumbling into decay could no longer be afforded.

Despite the glamorous history of this region, this is all state land now—wild everywhere except for the few remaining plots of ground where a building still stands. Uncas recently sold for seven digits, even though in all my times here I rarely see signs of life; the photos of the place in the online prospectus made it look quiet and dignified, like the ultimate backdrop for an L. L. Bean photoshoot. Sagamore, with its village of oversized log edifices, is now staffed by a platoon of earnest young grad students, employed on a contractual basis every summer to amuse and educate the weekly roster of flannelled guests. Only Kill Kare remains an exclusive private fiefdom, hidden from curious eyes behind a protective perimeter of posted signs.

The gentle, nearly level skiing came to an end when we came to a more prominent hill that led down to the wide bridge over the lake’s outlet stream. I let Paul get a little ahead of me before I zipped down after him. The powdery snow was a forgiving medium in which to play; when one of the fallen branches intruded into our path, even I was able to turn around it with grace. It made me feel, however momentarily, like a skilled skier.

At the bottom of the hill, a rather pointless brown sign, recently erected by the state, informed us we were leaving the “Historic Great Camps Special Management Area,” as if we were bidding farewell to some little hamlet back on Route 28. It stood beside the wide bridge spanning the outlet, built solidly enough for the small number of trucks that still drive this road. The icy stream below the bridge was darkened by the shadows of a coniferous forest; the lake itself was still out of sight, hidden just around a couple upstream bends.

A longer hill climbed away from the bridge. It was a bit of a trudge getting up this thing, but unless we chose a different route back to Sagamore we knew there would be at least one fun glide on the way back out.

Then our route circled southeastward, forced in that direction by a nameless hill that squeezed the roadbed close to the shoreline. The lake was not a sudden revelation, though. First a snowy little vly appeared to our left, the opening act for the main show. Then came an open expanse of ice, extending for acres and acres. Mohegan Lake!

Without another word I led the way off the trail and into the narrow band of forest that separated us from the icy plain. Unlike the hardwoods that had covered most of the road, here the balsams, hemlocks, and spruces had trapped the new snow above us with their branches, so the ground was barely covered. Our skis were like skinny snowshoes as we stepped over and around the forest detritus—although these “snowshoes” would happily betray us if we stepped the wrong way. It was an awkward few minutes, but there would be no better access further up the road. Although trees thickly lined the shoreline, I found one little opening where—if you successfully maneuvered a short drop and immediately ducked under an overhanging branch without falling on your tush—we had the best chance of reaching the ice without taking off our skis.

We glided out past the reach of the shadows to stand in the full sunlight, just a few yards off Mohegan’s southwestern shoreline. Camp Uncas, where J. P. Morgan once rusticated, could be seen on the northern shoreline, but otherwise every single acre within our field of vision was a wild one. It was a vast expanse of state-owned wilderness, all the way up to the frosty summit of Wakely Mountain to the east—only seven miles away, but with a barrier of thick forests and impassable wetlands between us. The fire tower could be seen on the summit, pointing upward like a dial to the faint quarter-moon on its heavenward trajectory.

Mohegan Lake: which may or may not have a sandy beach on its wild eastern shoreline, where I envision myself someday rinsing off the sweat of an August afternoon, with a can of beer safely stashed away in the cool shade, and my dog Bella daring me to grab the stick she is playfully holding in her mouth. Mohegan Lake: which has an inviting campsite atop a piney knoll on the north side—an inviting destination where, if I wanted, I could easily haul my pulk sled for a weekend of mild-weather winter camping, or my sixteen-pound Hornbeck canoe for some summer paddling. Mohegan Lake: where I have enjoyed this same view on several occasions over the last fifteen-plus years, but still have yet to do any of these things I have been contemplating.

Places like this are my landscapes of opportunity, where my dreams are more abundant than the time to execute them. This is what draws me back: the unrealized explorations and the unfulfilled experiences—that sense there will always be more to do and more to see when next I return. May my curiosity never wane, and may my strength sustain me for decades to come.

Mohegan Lake: where Paul and I stood and ate lunch on a sunny January day, listening to the distant drone of snowmobiles to the north on Raquette Lake, but choosing to enjoy instead the moonrise over Wakely Mountain.

Growth of a Forest

This was not our destination, though, just a scenic waypoint on an expedition into the heart of the forest. Bear Pond Road got its name by leading into a thousand-acre tract once owned by the Bear Pond Sportsmen’s Club, southwest of Mohegan Lake. In 1987, after a lumbering operation that reduced the forest to young saplings, the club sold the land to the state for inclusion in the Forest Preserve. The deal included an 11-acre use reservation around their two camps, which would expire after 35 years—and that thirty-fifth year, 2022, is now just around the corner.

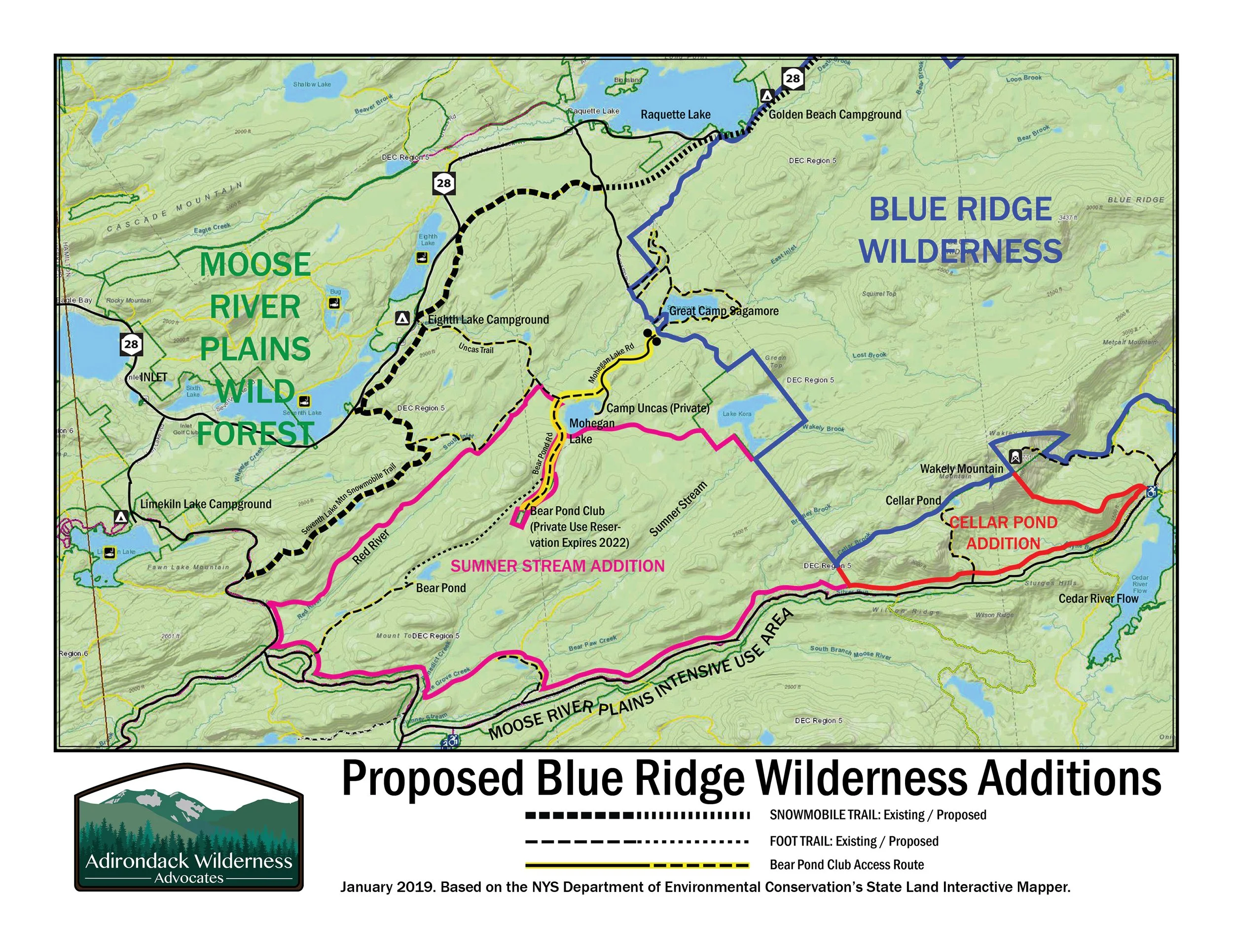

This parcel came to mind recently when I proposed that it become part of an 18,000-acre addition to the Blue Ridge Wilderness, in response to the state’s proposal to construct a snowmobile trail further north near Golden Beach. While a route that more or less parallels Route 28 is not a completely horrible place to put a snowmobile trail, it would still create an inroad into the protected wilderness, measuring about 500 feet deep and as much as four miles long. Any loss of wildness, however small or peripheral, is still a loss.

Therefore it makes sense to offset that loss with the closure of something else—preferably, an existing motor vehicle route in a remote area, a place with a high potential to offer a true wilderness experience. And thus this old road, which is due to become obsolete anyway on March 26, 2022, came to mind. Although not currently used by the public, it has nevertheless been considered (and passed over) for at least two non-wilderness uses in recent years. A land reclassification would permanently remove it from all future considerations, once the club no longer needs it.

So if I had my way, the Blue Ridge Wilderness would be allowed to outgrow its current boundaries, which were arbitrarily drawn many years ago between Lake Kora and Wakely Mountain. The wilderness would sweep southwestward, engulfing tiny little Cellar Pond in its high mountain basin, then down along the length of Sumner Stream almost all the way to the Moose River Plains campsites. With nothing more to stop it, the Blue Ridge Wilderness would continue growing westward until it reached the little Red River, which follows a straight-as-an-arrow fault line past the foot of Seventh Lake Mountain to the Moose River.

I speak fancifully, as if the wilderness must overtake these places and make them wild, like a green invasion force. In reality this region is already sufficiently wild, to the best of my knowledge. I have to qualify my assertion with the admission that I barely know the area; all of this proposed new wilderness is far removed from the nearest pavement, and its entire southern edge is only accessible in the summer and fall. This is not a region I have visited often, but what I have seen has made an impression.

The first rule of wilderness advocacy is to always know firsthand the landscape for which you are advocating. If you have never walked the land and experienced it for yourself, you will never be able to competently communicate the need for its preservation to others, or inspire them to see the need as urgently as you do. Your arguments will be purely hypothetical, like the cold calculations of a chess player, and your words will ring falsely even in sympathetic ears.

In the case of Bear Pond Road—the best access from the north to the vast wilderness beyond Mohegan Lake—I had been here only once before. That was on January 1, 2004, according to one of my journals. On that day fifteen years ago I had been in search of a view from the top of a steep ridge that runs behind the club’s reservation, and I had used Bear Pond Road as the springboard for my bushwhacking proclivities. I never did find the open ledge I was looking for, but my notes from that day tell me I did get a look at both of the camps on my way through. Reading my descriptions of them years later, I realized their images had long since faded from my memory.

Therefore it was now timely that I returned. Paul and I followed our tracks off the lake and returned to the road, which extended nearly another two miles to the inholding. The ski conditions remained grand, with the old snow forming an impenetrable base underneath the fresh powder. Skiing can be a finicky pursuit, requiring the right alchemy of temperature and snow quality to be enjoyable, so not skiing on a day as perfect as this would have been sinful.

I had remarked in my journal from 2004 that the boundary with the club’s former lands was obvious by virtue of the abrupt change in forest cover; this area had been logged heavily before state acquisition, and I wrote that it bore a striking resemblance to the high-graded forests up near Little Tupper. That suggested that I saw lots of saplings that day, lots of scrubby woods. If so, the last fifteen years had apparently been one of growth, as I could no longer detect such a stark contrast. We were hardly skiing through an old-growth forest, but the trees we saw today were not anemic, either. The scrub was maturing into something nice. Have my Adirondack experiences really grown so long in the tooth that I can now perceive the regrowth of an entire forest? There’s a scary thought!

A short driveway led to the first of the two camps, a modest little cabin with views of nothing but the thick balsam fir stand that surrounded it. This was Camp Spread Eagle, according to the sign on the porch; a yellow diamond placard, like a mock highway sign bearing the picture of a forlorn stick figure with its head hung low, jokingly warned that this was a “depressed deer hunter” crossing zone. The cabin looked like a cozy hideout, the kind of place where you could kick up your feet next to a woodstove and pass the time without a care.

Another fifteen minutes of level skiing, as we popped in and out of some small clearings, brought us to the second camp at the end of the road. This one was a bit of a monstrosity by comparison, two stories tall and completely encased with corrugated aluminum; you could probably cook a hot dog inside without even trying on a sunny summer day. This spot was a total of 4.9 miles from where we had first donned our skis; despite the name of the club, Bear Pond itself was still several miles deeper into the woods, well out of our reach today.

The Road to Wilderness

So the question is this: Does the Bear Pond parcel need to be wilderness? Some people might doubt the value of reclassifying an existing piece of state land just to achieve more wilderness acreage. If there are no known threats, and no expectation of non-conforming uses after the club’s camps are removed in 2022, then the act of reclassifying the land to include a place that is already wild is an empty exercise. And for the sake of full disclosure, I should mention the Bear Pond parcel has been part of the Moose River Plains Wild Forest ever since its acquisition, back when Ronald Reagan was still president.

But the point of a wilderness classification is to protect isolation—to preserve as much as possible these deep-woods buffers from modernity, where even a citizen of the tech-crazed twenty-first century can look up and see a sky filtered only by the web of a forest canopy. Article XIV of the state constitution does a good job protecting trees from being cut for human consumption, but it doesn’t say a word about preserving the off-the-grid experiences many of us implicitly expect from a so-called “wild forest.” Additional management guidelines must be layered on top of Article XIV to achieve those goals.

For much of the last century, the old Conservation Department used to defer to the opinion of the sitting Attorney General to interpret the constitution and decide what was and was not allowed in the Forest Preserve. Rental cabins were out, but rustic lean-tos and tent platforms were permissible, for instance. Later, this advisory role was assumed by the Adirondack Park Agency and its State Land Master Plan—although this institution has always been more concerned with sustainability, and not the legal nuances of the state’s master charter.

Issues of motorized access to the Forest Preserve began in the 1930s, when the state and federal governments constructed fire truck “trails” deep into the backcountry. To those who challenged these inroads, it was pointed out that the whole point of the Conservation Department, nee the Conservation Commission, had been to implement a fire protection program that would prevent a repeat of the disastrous blazes of 1903, 1908, and 1913. The truck trails were an outgrowth of the same mandate that gave us a network of fire towers, which no one ever questioned.

Motorized recreation on the part of the public became a problem after World War II, when more than a few people traded their boots and snowshoes for jeeps and snowmobiles. State land managers were quick to assume these were allowable uses, completely unrelated to the logging prohibition required by Article XIV. Others cried foul, assuming the exact opposite: that the word “wild” in the phrase “forever kept as wild forest lands” implied a ban on motors.

But here’s the thing: in all these years, no one has dared asked the question of whether motors are constitutionally allowed in the Forest Preserve—at least not out loud, and not within the confines of a court of law. Even the recent lawsuits regarding the use and construction of snowmobile trails have intentionally danced around this fundamental question—which no one wants to ask, on either side, for fear of what the answer might be.

Therefore the wilderness classification, as currently defined by the State Land Master Plan, will remain relevant as long as anybody expects and demands a quiet experience in the Forest Preserve, unmitigated by gears and motors once you leave the trailhead parking area.

And if places like Bear Pond exist now essentially in a wilderness state, this does not mean there haven’t been threats—or that there won’t be again. For instance, the road that Paul and I skied today was one of the alternates considered for a snowmobile trail that was ultimately constructed on Seventh Lake Mountain. The state’s final route selection did spare Bear Pond from direct motorization, but the proximity of the Seventh Lake Mountain Trail has nevertheless brought motorized recreation about a mile closer to this otherwise secluded area than it had been previously.

Then there was the report commissioned by the Department of Environmental Conservation in 2013 to assess the Moose River Plains Wild Forest for its potential as a bicycling destination. The author of that report was the International Mountain Bicycling Association based in Boulder, Colorado; and as you might expect from an out-of-state special-interest organization—with no ties to our local area, no knowledge of the existing uses in these hinterlands, nor any interest in the unique conservation history of the Moose River Plains—the IMBA miraculously found suitable backcountry trail locations everywhere, including the Bear Pond parcel. The report read like a long list of stock suggestions, many of which could have been applied to an abandoned golf course with little modification.

So wilderness protections in this case would matter, even if the gains seem subtle. As long as this secluded, out-of-the-way corner of the Adirondacks remains classified anything other than wilderness, it remains exposed. The State Land Master Plan encourages us to focus recreational development in wild forests, so someone will eventually see this old road and devise a use for it.

A Long and Gentle Run

The corrugated cabin cast a cold shadow in the snow, prompting Paul to back into the sunshine before opening his pack and retrieving his stash of snacks. I had filled an insulated bottle with Stewart’s coffee on my drive north this morning, and I now finished the last of it; the chilly day had taken the steam out of the coffee, but it still tasted good. I could see a snowy beaver meadow beyond the cabin from where I stood, and ever the trip planner, I immediately thought of setting forth to investigate. But I knew better than to suggest it.

“Well, do you think we should start heading back?” Paul asked.

It was still midafternoon, but at this time of year midafternoon is a rather late hour to be five miles from your car. The winter sun is a low-flying orb that never quite clears the treetops, to the extent we see it at all; pale and distant compared to its summer self, it seems bound to the horizon by an invisible chain of gravity. The sunrises are late, the sunsets are too early, and even a native of this latitude never fully embraces the concept of darkness arriving by five o’clock.

“Yeah, we’ve got a ways to go,” I agreed, putting the now-empty bottle back in my pack.

We hoisted our packs onto our backs, grabbed our poles, and turned our skis toward the tracks we had made just a short time ago. Although it’s a sad moment on any trip to reach the point where you must turn around, there is always something to look forward to on a ski trip. Whereas we had been breaking trail for most of the trip past Mohegan Lake, we now had our own tracks to follow, meaning there would be more gliding and less trudging as we made our way back to Great Camp Sagamore.

A subtle uphill led us away from the camp made of corrugated metal, and then we strode through the little meadows still filled with sunlight. To the right and left were dense, unbroken stretches of forest, with no sight of the long ridgeline I had climbed fifteen years ago to the west. Nor was there any indication of the complex maze of wetlands to the east, which I only knew from studying topographic maps; in that direction was a country I had never laid eyes upon.

I wondered who else would be attracted to a place like this, once the camps are removed. Unless the state erected a lean-to at the site of one of the cabins, or perhaps extended the trail all the way to Bear Pond itself, there would be little incentive for the average person to continue past Mohegan Lake. Although Paul and I were impressed today with the ski conditions, most people would balk at the idea of a dead-end trail to nowhere.

But I could imagine a worse fate than allowing the Bear Pond parcel to become a blank spot on a map, far removed from the centers of human population and commerce. If this happened, the land would satisfy the concept of wilderness as Aldo Leopold once understood it.

The forest canopy closed over the road in a cathedral-like arch as we skied along, and I knew that we had passed the former boundary line. The old road dropped on a gentle grade back into the Mohegan Lake basin, and because Paul was the faster skier I happily let him glide well ahead of me. It was a long and gentle run, all of it seemingly away from the sun. There were only two dead stops: once to step over a tree that had inconveniently fallen across the way, and another to step across a rogue rivulet that was flowing across the surface rather than through one of the hidden culverts.

I found Paul waiting for me at the bottom of the hill, with the open expanse of Mohegan Lake once again visible through the trees.

“Do you want to just keep to the trail?” he asked. We had talked before about the possibility of a shortcut across the lake, but that was before we had seen the hill leading down to the bridge over the outlet—a slope covered with a silken layer of powdery snow, and not much else. We had trudged up it a few hours ago, and I could tell it had made an impression on both of us. If you ski up a hill, the mandatory reward is to ski down it.

“That works for me,” I said, and a moment later we were off, saving the exploration of Mohegan Lake for another time. On this fine January day, the hill beckoned—and we were too weak to resist.